UK schools struggle to support children with autism

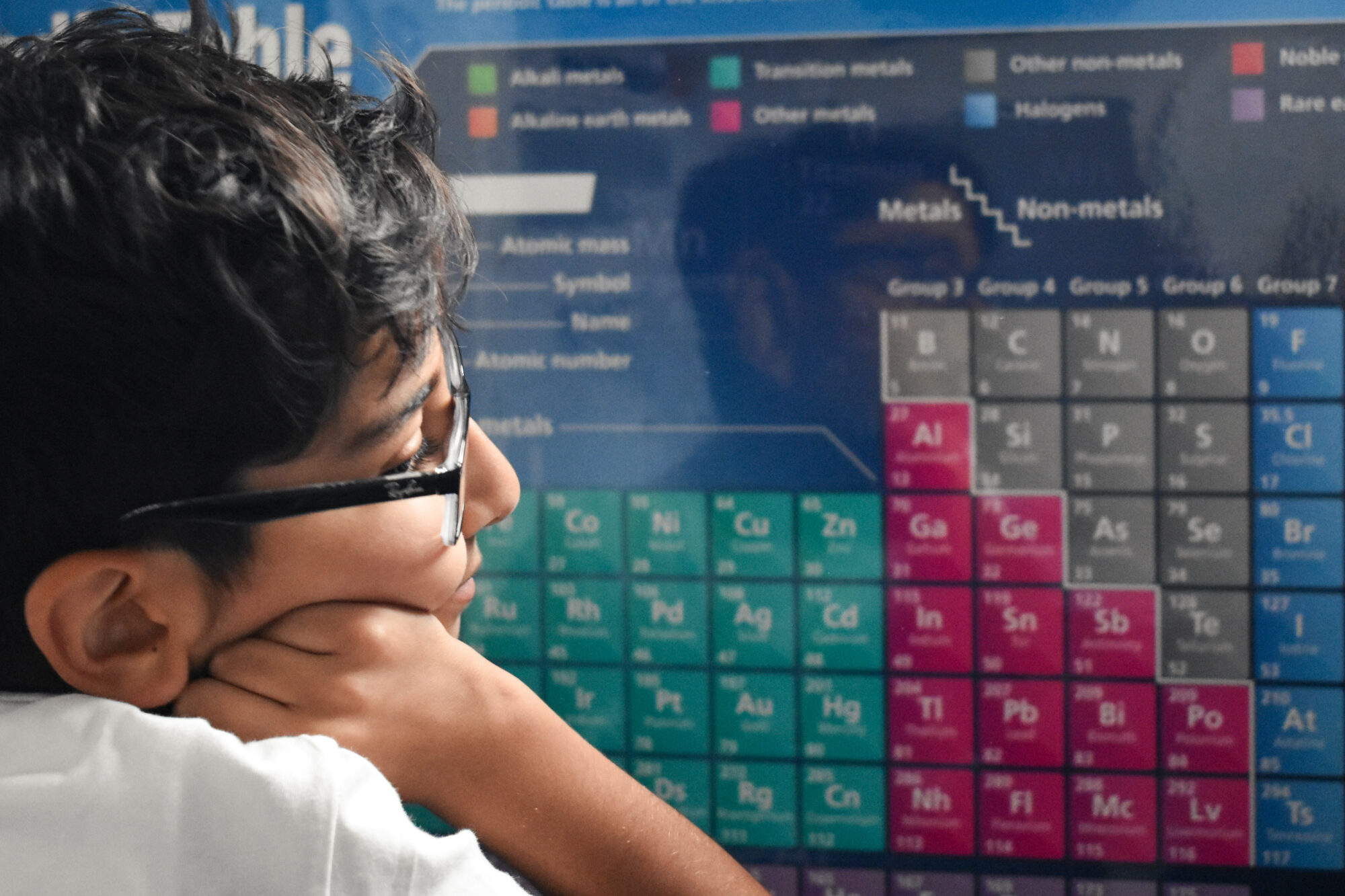

A boy in a yellow polo shirt sits quietly at a desk at the back of his classroom. During the school day, a quick “brain break” – where he takes five minutes with sensory toys and his support teacher – gives him a reprieve from the buzz of 30 classmates and his teacher’s instructions. For Umar, and thousands of students like him across the UK, this is not a luxury. It’s something he needs to be able to learn like his peers.

“The way I explain it is that Umar is more than capable of learning and being understood. His brain is just wired differently,” says Fozia Riaz, his mother, who lives with nine-year-old Umar, his siblings Ayesha and Usmaan, and their father, Saad, in Brighouse, West Yorkshire.

Umar is the youngest of my cousins. He was diagnosed with autism towards the end of nursery, and nobody knew how it might impact his life. All we hoped was that that bright-eyed, curious child would stay bright-eyed and curious. As it turns out, he has been one of the luckier ones.

A failing system

A big part of the problem lies in delays around education, health and care plans (EHCPs). These are legal documents, similar to individualised education plans (IEPs) in the US. In England, they’re used to clarify the support a child with special educational needs (SEN), including autism, is entitled to receive.

But across the country, that system is failing. As of 2024, only 46% of EHCPs were issued within the legal 20-week deadline. When a child needs extra support but cannot present an EHCP, schools often can’t access extra funding or specialist assistants to help them.

In 2024 the National Audit Office warned that the UK’s SEN system was “financially unsustainable”. Councils face multi-billion-pound deficits by 2028. Policymakers, local authorities and school leaders need to address funding shortfalls so that schools can cover specialist training and equipment. With an increasing number of students being diagnosed with autism, schools are under more pressure. That means autistic pupils like Umar and their families have to use their own time and money to fight for the help they’re entitled to, while teachers try to juggle students’ additional needs without adequate training.

Overstimulation, not disruptiveness

Mainstream education (state run, non-specialist schools that serve the general student population, as opposed to SEN-specific schools) seemed a good fit for Umar. But elements of everyday classroom life started to get overwhelming.

“If they said something like, ‘Umar, can you go get your books out of your drawer and then come sit on the carpet?’, it became too much of an overload, especially with the noise of the classroom,” says Fozia.

Teachers started to label Umar “disruptive.” It took sustained advocacy from Fozia for the school to implement basic accommodations, such as visual timetables or noise-reducing headphones.

Between 2023 and 2024, the number of SEND (special educational needs and disabilities) tribunal cases increased by over 50% across the country. That means parents are turning to the UK’s independent national tribunal to deal with disputes over wrongful suspensions, suitable accommodations, or trouble receiving an EHCP. It’s clear that mainstream schools have struggled to cater to neurodivergent students. Parents and students need help, and they’re not getting it.

One size does not fit all

Umar’s early years at school passed smoothly. At the age of five, his routines were simpler. There was less room for overstimulation, so it was easier for support staff to help him. When he moved up to Year 2, an unexplained reshuffle of his classroom upended his sense of safety. Fozia recalls her son telling her: “I don’t wanna go to school, I hate school, I don’t like it.” It took eight months for Umar to settle again.

“He needs routine. He likes the structure, he likes to know what’s happening,” says Fozia. “At the beginning, I really struggled to get my voice heard. I actually ended up in tears with the teachers. After that event, I had a bit more of a backbone.”

Now, she says the school listens better, but she remains vigilant. Umar, ambitious as ever, has big dreams. “He wants to go to Mars. I know he’s very clever,” his mother says. “It’s just whether we are able to unlock that – help him understand the world and help the world understand him.”

“Parents and students need help, and they’re not getting it.”

View from the back desk

From his spot at the back of the room, Umar describes what school is like for him. “What I like most about school is playing with my friends, learning about something exciting, especially imperial units. I like music. I like my reward time.”

When his tasks pile up, teachers help him out: “They remind me what to do when there’s too many instructions,” he says. His “brain-break” cupboard, equipped with magnets, counters and his toy puppet, “Foxy”, is nearby.

Aimee Scott, Umar’s main class teacher, has adapted her methods since meeting him. It was her first experience with an autistic student. She says she’s learnt that “all autistic children are extremely different, but I believe the most crucial thing is building trust and support with that child and helping them to understand that you are there to support their needs.”

In her classroom, she uses visual timetables, social stories (Umar uses images and captions to help him prepare for things like moving to a new classroom or interacting with new classmates) and one-to-one “talk time” to prevent overstimulation in her neurodivergent students.

But the problem is bigger than just her classroom

“Mainstream primary schools are particularly struggling with funding to support children with autism and SEN,” says Scott. “This needs to be made a priority as these children have specific needs and require very personalised support.”

“I know that Umar will grow up to do brilliant things. I only hope every autistic student has that chance”

Keeping mainstream options open

Nirvana Yarger is a special educational needs teacher who provides a tailored curriculum to neurodiverse students outside mainstream schools, through her organisation Community Classroom, based in London.

“While their academic needs are met more often, other needs can have a serious impact on how much autistic students are able to actually learn – for example, if their anxiety is high,” says Yarger. That was exactly the case for Umar, who’s been achieving high grades but needed social support.

She flags EHCPs as a shortfall. “I once worked in a school where the waiting time to see a local authority educational psychologist was 30 months,” she says. “It’s no wonder so many children struggle.”

But small things that can make big differences, Yarger tells me, such as flexibility in school policies on attendance or school uniforms.

While SEN-specific schools have their benefits, particularly for students with more extreme needs, it’s important for mainstream schools to remain an option. These schools offer a chance for neurodivergent students to benefit from better social integration, broader access to resources, and are often easier for parents to access.

Umar’s experience proves that autistic students can thrive in mainstream schools with the right support. When I ask Umar about his future, he tells me, “Last Friday, I did a transition day to see how it was in Year 5, and it was really good, so I’m really excited to go to Year 5. I met the teacher and she was really nice.”

I know, thanks to his family, school, and himself, that Umar will grow up to do brilliant things. I only hope every autistic student has that chance.