Spotlight on schools where disability is not an obstacle

When I was 7 years old, my science teacher often stood in front of the class and imitated how I walked. As a result, my classmates would laugh at me. No one comfortably shared a seat with me or played with me. Some believed I would pass on my disability to them. This made me very uncomfortable in school and affected my performance, especially in science. My parents struggled to find a school that would accommodate my educational needs – there were no inclusive schools in my community.

Such barriers affect many students with disabilities in my school and neighbouring schools. Throughout Africa, less than 10% of all children with disabilities under the age of 14 are attending school. In Uganda, only 5% of children with disabilities can access education through inclusive schools and 10% through special schools, according to the latest available figures from Unicef. Article 30 of the Uganda constitution emphasises education as a fundamental right for everyone, and all primary schools funded by the government are given ‘facilitation grants’, 10% of which should be used on special needs education. Sadly, school management committees often not plan for the needs of students with disabilities.

“Throughout Africa, less than 10% of all children with disabilities under the age of 14 are attending school”

Amazingly, schools like Good Samaritan Inclusive Primary School are ensuring that children with disabilities can reach their full potential. A boarding school for students aged four to 25, it is located in Mukono district, on the outskirts of Kampala. According to the school administration, it’s one of only two schools embracing inclusive education in central Uganda. It was initiated in 2005 by Fred Migadde, the school director. Of the 167 students, 57 have disabilities including physical disabilities, albinism, cerebral palsy, hydrocephalus, spina bifida, autism, mental impairments, sickle cell, Down syndrome, speech impairment and visual impairment.

The teachers and students are empathetic and supportive: when I visit, I see students with physical disabilities being wheeled by students without disabilities happily from their classes to the dining room and back to their classrooms.

Racheal Safali, the school administrator and a special needs education teacher, says that when the school first opened, they would recruit teachers without fully assessing their skills in inclusive education, which sometimes led to discriminatory behaviour. “A mere look at saliva drooling from a student’s mouth was enough to make that teacher have a negative attitude,” says Safali. “We now ensure that all staff recruited are fully trained on how to handle special needs students.” The school also educates parents, caregivers and neighbouring communities about the unique and diverse educational needs of students with disabilities.

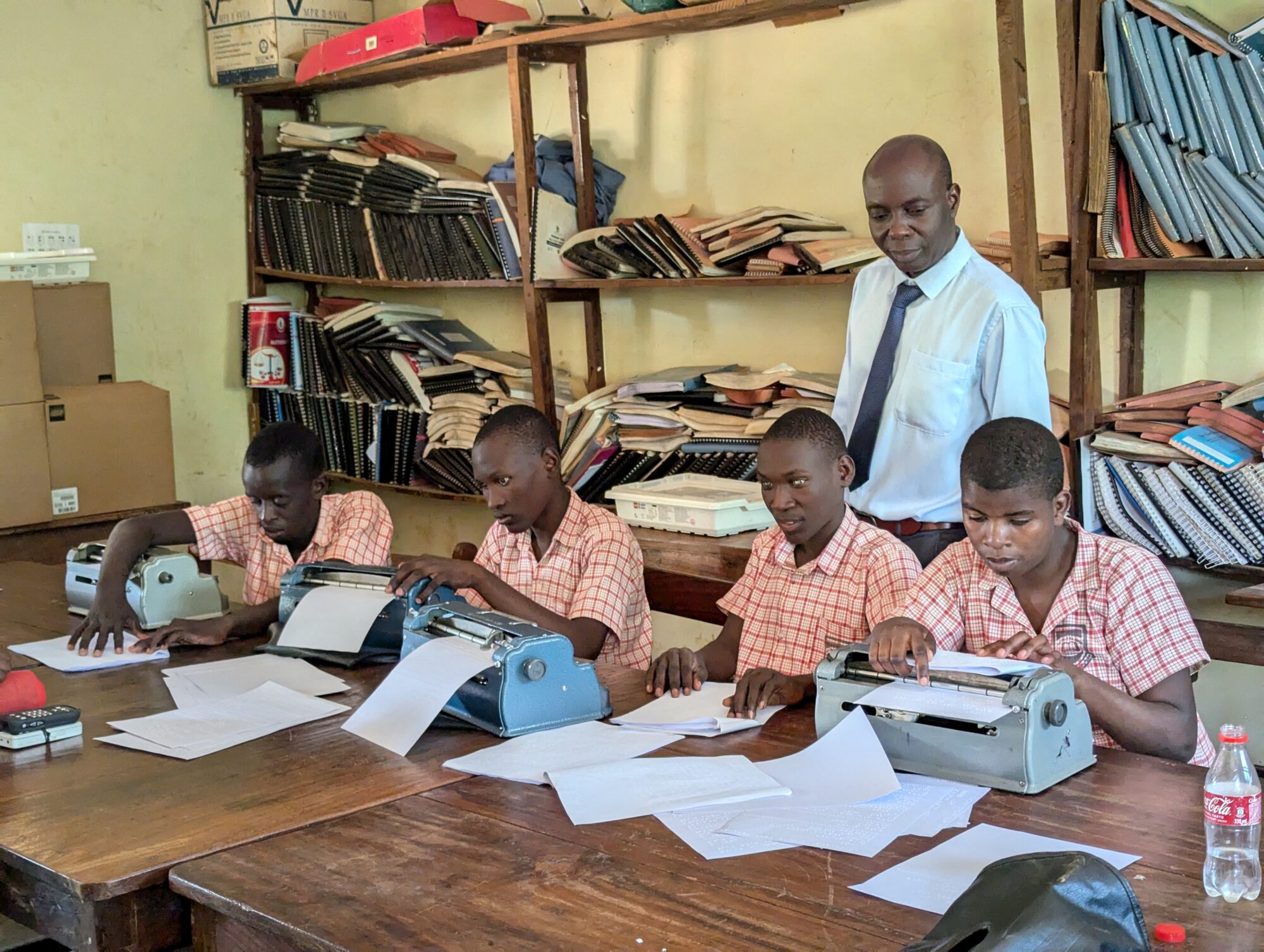

Other schools in Uganda also show what inclusive education can look like. Basalirwa Richard, a special needs education teacher at Bishop Willis Demonstration Primary School, Igan district, enrolled in 2014 after realising the school didn’t have enough teachers. “This has been my most rewarding experience. I have used my skills to make the education of blind students accessible,” he says. Like Good Samaritan Inclusive, at this school students with and without disabilities learn together.

Skills, sport and support

Good Samaritan Inclusive does not only focus on academic learning. Students also learn vocational skills like weaving, tailoring, art and craft. They are taught how to make briquettes and charcoal-efficient stoves. They sell the products to their caregivers and visitors during school functions like sports competitions, and the school uses the money raised to buy them gifts and essentials like diapers, especially for students with spinabifida and severe cerebral palsy. “Even if some of them are not in a position to enrol for further studies, they have the skills to en them to live independently,” says Safali.

The school also has an inclusive play and sports staff member, Veronica Matinyi. Students with disabilities participate in sports such as wheelchair racing and bottle filling – empty bottles are lined up near buckets of water and the student who fills up the most bottles before the whistle is blown is the winner. “Our students have also had opportunities to compete with other schools in these sports… They won a trophy at Kaazi scout camp in 2023,” says Matinyi.

Matinyi assesses each student who starts at the school by getting information detailing their disabilities including prenatal and postnatal history, and family social history. “Some caregivers just bring their children to school with little or no information at all regarding their children. Moreover some parents are told by their neighbours that their children have disabilities because of witchcraft,” says Matinyi. “I explain to each parent about their children and their disabilities, and this helps change their attitudes.” The information she gathers is also used by teachers to offer individualised support, and by the national examination board during exams.

“Some students are brought to school when they have very low self-esteem… now, they boldly ask for whatever they need from their fellow students and teachers”

Abdul Karim Ssozi, a 15-year old student at Good Samaritan Inclusive, describes how a student laughed at his disability at his former school. “I felt bad and reported him to the teacher. He counselled me and encouraged me to read hard and pay no attention to such people,” says Ssozi. Despite the teacher’s intervention, students kept making fun of his disability. His parents decided to look for a different school; Good Samaritan Inclusive was the answer.

“The teachers here are so friendly, all students know each other’s disabilities and the challenges they face and no one laughs at one another,” says Ssozi. His academic performance has greatly improved. His best subject is social studies – he vividly remembers his best mark in social studies being 65% at his former school. Now it is 92%. Ssozi aspires to be a lawyer, so that he can advocate for the rights of people with disabilities and the elderly.

Matinyi says inclusive education plays a vital role in building confidence. “Some students are brought to school when they have very low self-esteem. Some cannot even speak to their fellow students or teachers. Some would just keep quiet even when they need something to eat. Right now, they boldly ask for whatever they need from their fellow students and teachers,” she says.

Despite its transformative power, the school is overwhelmed by resource constraints. Most of the caregivers and parents of these students cannot afford school fees, textbooks, pens and personal requirements such as diapers for their children. As a result, the school has to help. There are insufficient special needs teachers; the school needs more dormitories and meal costs are high.

The Good Samaritan Inclusive school administration would like the government to cover some costs around food, accommodation and books. Ssozi suggests reducing taxes on diapers. He also wants the government to recruit more special needs teachers and build more school buildings.

Goretti Byomire, director of the Disability Resource and Learning Centre at Makerere University in Kampala, says: “Very many buildings including classrooms are physically inaccessible to students with disabilities, and the digital technology is often not captioned and brailed, making students with visual impairments excluded.”

Following my own experience, I decided to advocate for inclusive education. In secondary school, I worked with visually impaired students to advocate for accessibility, and at university I spearheaded the formation of Kampala International University Association for students with disabilities. And, despite the odds, I successfully pursued a career in medicine and surgery.