An inclusive school changed everything for one girl with Down syndrome

Narin Mohammad entered motherhood in her early twenties, when she was, in her own words, a sheltered Syrian expat living in the UAE. She never left her parents’ house before marriage to venture on her own and was unaware of the journey that lay ahead of her.

Melia, her first born and only child, was diagnosed with Down syndrome three months after her birth. “It was a shock for me,” Narin says. “I was already struggling with post-partum depression, and the added news took a toll on me. I was so scared for her future. I kept asking myself: would she ever be independent? Would she ever go to school normally?”

Approximately 21 people out of every 100,000 are born with Down syndrome around the world, yet despite being a highly prevalent group, traditional education systems in many countries are not adapted for their needs. Children with Down syndrome face a plethora of barriers that prohibits them from accessing inclusive and accessible education that would greatly improve their future earnings, social skills, and ease into society. This ranges from a lack of teacher training, attitudes and stigma towards them, and resource constraints.

But what happens when an education system is accessible, inclusive, and caters for a child with Down syndrome’s needs and development? How does this impact their mental wellbeing and future prospects?

“Everyone was opposed to my decision. Our family, friends and even Melia’s father. I never had doubt”

Now aged seven, Melia is a favourite in her school, able to read, write her name, and has progressed to the second grade alongside her peers.

This came with a large range of setbacks, challenges, and risks that Narin took, alongside access to inclusive education that the UAE provides.

Melia was cared for by a nanny during the first few years of her life. “She taught her the alphabet, colours, and shapes, and her social skills and even walking ability improved after she was integrated with other children her age. She started to challenge herself to go on slides when she saw other kids her age doing so.”

Unknowingly, Melia was reaping the benefits of integrated learning, a form of education where children with developmental disabilities are placed alongside their typically developing peers. A key area in childhood development is play time, which allows children to develop a rich array of social skills. Research has indicated that children with developmental disabilities have up to a 30% increase in communication skills when exposed to peers exhibiting model typical language.

When time had come for Melia to enroll in her first year of school, her mother put her in a Segregated Special Education School, a school designed to accommodate a wide range of disabilities, and which caters solely for disabled children.

“I noticed a mild improvement in her learning abilities, but I was concerned,” Narin says. “I believed her environment and peers would set the benchmark for her, and I wanted her to further challenge herself to grow. How will Melia integrate into normal society, if she is never placed into one?”

Within a year of Melia attending the Segregated Special Education School, her mother decided to place her into an inclusive school, where both disabled and non-disabled students learn together. This was difficult for her to find, as not all schools were able to cater to the needs of children with disabilities.

“Everyone was opposed to my decision, our family, friends, and even Melia’s father, however, I never had a moment of doubt, I knew what was best for my daughter as her mother,” says Narin.

With weekly physical and speech therapy classes, being placed into a school for typical peers that also supports children with disabilities, and after-school learning from her mother and father, adapted to her needs – Melia thrived.

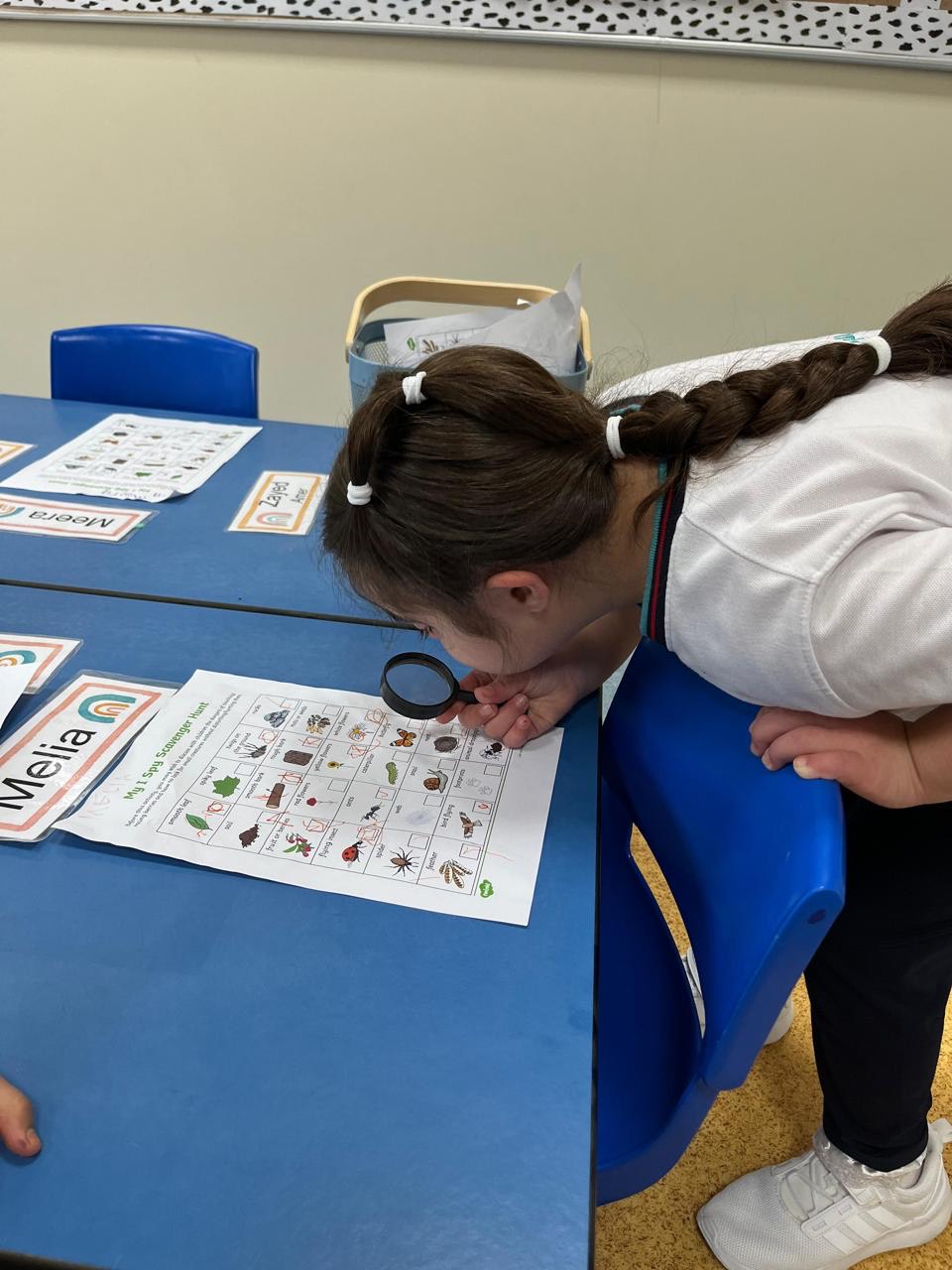

Melia was placed in a classroom alongside neurotypical peers, where a special educational needs (SEN) certified teacher (responsible for assessing, planning and monitoring the progress of children with special educational needs and disabilities) was responsible for giving her 45-minute, one-to-one weekly classes, designed for Melia’s specific needs.

The physical education classes helped Melia learn how to hold a pencil and use it to write, a skill people with Down syndrome can struggle with due to physical differences with their motor skills. Her speech therapy classes helped her language and speaking abilities.

“I used to worry that Melia would never attend school, now I imagine her graduating high school just as any other peer of hers”

The Head of Kindergarten and Primary of Melia’s school described how the school accommodated Melia and her needs. “Our school is committed to inclusive education by implementing individualised education plans, offering in-class support from learning support assistants, and providing access to therapy and intervention services where needed. We use differentiated instruction, assistive technology, and flexible classroom environments to ensure students with disabilities can participate meaningfully in learning. We also promote collaboration between classroom teachers, special educators, parents, and specialists to create a supportive, student-centred learning experience.’’

Narin now beams with pride and joy when speaking of how inclusive and integrated learning has changed Melia’s life outcomes, outcomes that have improved due to early intervention, intensive treatment, and being treated as a capable individual.

“I used to worry that Melia would never attend school, now I imagine her graduating high school just as any other peer of hers.”